Viral Infections

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Influenza Viruses

Overview

Three types of influenza viruses primarily infect humans: A, B, and C. Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes based on two surface proteins, hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). Influenza A viruses can infect animals and humans and produce epidemics and pandemics. Influenza B viruses only affect humans and cause yearly epidemics but not pandemics. Influenza C causes mild illness and does not cause epidemics.

Minor changes in the H and N surface envelope glycoproteins (antigenic drift) of influenza A and B viruses cause yearly epidemics, and major changes (antigenic shift) in influenza A after genetic recombination from animals cause global pandemics. The last influenza pandemic occurred in 2009 and was caused by H1N1. Emerging subtypes of importance include H7N9, which circulates among poultry in China and can cause severe illness in humans; H5N1, which infects humans through close contact with infected poultry and can spread from person to person; and variants circulating in pigs that can sporadically infect humans.

Clinical Features and Evaluation

During the winter, influenza A causes a self-limiting illness with fever, cough, rhinorrhea, myalgia, and headache in most patients; influenza B causes a milder illness. Older adults (>65 years), young children, pregnant women, and patients with chronic medical conditions (especially chronic lung disease) are at higher risk for severe primary influenza, complications such as superimposed bacterial pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or Staphylococcus aureus, and death (see Community-Acquired Pneumonia). Less common but severe complications include asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations, myocarditis, encephalitis, rhabdomyolysis, myositis, sepsis, and multiorgan failure. Parotitis caused by influenza was reported during the 2015-2016 influenza season.

During the endemic season, patients can be diagnosed within 20 minutes using either rapid antigen tests or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of nasopharyngeal swabs. Both tests are highly specific, but PCR has a sensitivity of nearly 100%; the rapid antigen tests have a sensitivity between 59% and 93%. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has recently published updated guidelines for seasonal influenza evaluation and management. The IDSA guidelines recommend using PCR over rapid antigen tests. During seasonal influenza activity, testing for influenza should occur in patients at high risk who present with influenza-like illness, pneumonia, or nonspecific respiratory illness if the testing result will influence clinical management (decisions on antiviral treatment initiation, impact on other diagnostic testing, antibiotic treatment decisions, and infection control practices). Patients at highest risk for influenza-related complications are those older than 65 years, patients with chronic medical conditions, immunocompromised patients, pregnant and postpartum women, those with a BMI of 40 or more, persons with neuromuscular disease, and residents of extended-care facilities. Other outpatient candidates for testing include those who present with acute onset of respiratory symptoms and either exacerbation of chronic medical conditions or with known complications of influenza, such as pneumonia, if the testing result will influence clinical management. During times of influenza activity, testing for influenza at hospital admission is recommended for all patients with acute respiratory infection and in patients with acute worsening of chronic cardiopulmonary disease. In all cases, treatment decisions should not be delayed pending confirmatory results.

Management

The IDSA guidelines recommend initiating antiviral treatment as soon as possible for adults with documented or suspected influenza who are hospitalized and for outpatients with severe or progressive illness regardless of illness duration. Treatment should also be initiated as soon as possible for all other patients at high risk for influenza-related complications. Treatment can also be considered for otherwise healthy outpatients if started within 48 hours, household contacts of severely immunosuppressed patients, and health care workers who care for patients at high risk of developing complications from influenza.

Neuraminidase inhibitors are active against influenza A and B and can be given orally (oseltamivir), intranasally (zanamivir), or, more recently, intravenously (peramivir). Antiviral therapy should be given for at least 5 days, but in severely ill or immunosuppressed patients, a longer duration should be considered with repeat follow-up testing to document clearance. Immunosuppressed patients are at risk for neuraminidase inhibitor resistance during or after therapy.

Baloxavir is a polymerase acidic endonuclease inhibitor that can be given as single-dose therapy for uncomplicated influenza. It must be started within 48 hours of symptom onset and appears to be as effective as a 5-day course of oseltamivir. In October 2019, baloxavir was FDA approved for the treatment of patients at high risk of influenza complications; its effectiveness in hospitalized patients with severe influenza has not been established.

Widespread influenza vaccination is the most important preventive intervention; all persons aged 6 months or older without contraindications and all health care personnel should be vaccinated (see MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine). Oral oseltamivir and baloxavir and inhaled zanamivir are FDA approved for chemoprophylaxis (zanamivir is not approved in patients with chronic lung diseases) to contain outbreaks in institutional settings (such as long-term care facilities) and hospitals in conjunction with droplet precautions and vaccination. Chemoprophylaxis should be initiated as soon as possible and no later than 48 hours after exposure and should be continued for 7 days after the most recent exposure. Good hand hygiene and face masks can prevent secondary infections in households.

Novel Coronaviruses

Coronaviruses are RNA viruses that cause respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases. Six known types infect humans, with some infecting animals as well. Two novel coronaviruses, severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome–coronavirus (MERS-CoV), can infect animals and also cause severe disease and epidemics in humans. In 2002, SARS-CoV emerged in China, causing an acute pneumonia epidemic with a mortality rate of approximately 10%. No infections have been reported since 2004. Treatment is supportive. MERS-CoV emerged in 2012 in Saudi Arabia in humans and camels, with most infections occurring in the Arabian Peninsula. MERS-CoV causes pneumonia, diarrhea, and kidney failure with a mortality rate of approximately 40%. Because all types of coronaviruses may spread from human to human, contact and airborne precautions should be implemented for hospitalized patients with suspected infection. In December 2019, a new coronavirus emerged, severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). It is associated with a spectrum of illness, from asymptomatic, mild disease to pneumonia and respiratory failure, particularly in older adults and those with underlying medical conditions. SARS-CoV-2 spread quickly, leading to a worldwide pandemic. For the most current information, please see COVID-19: An ACP Physicians Guide and Resources (https://assets.acponline.org/coronavirus/scormcontent/).

Human Herpesvirus Infections

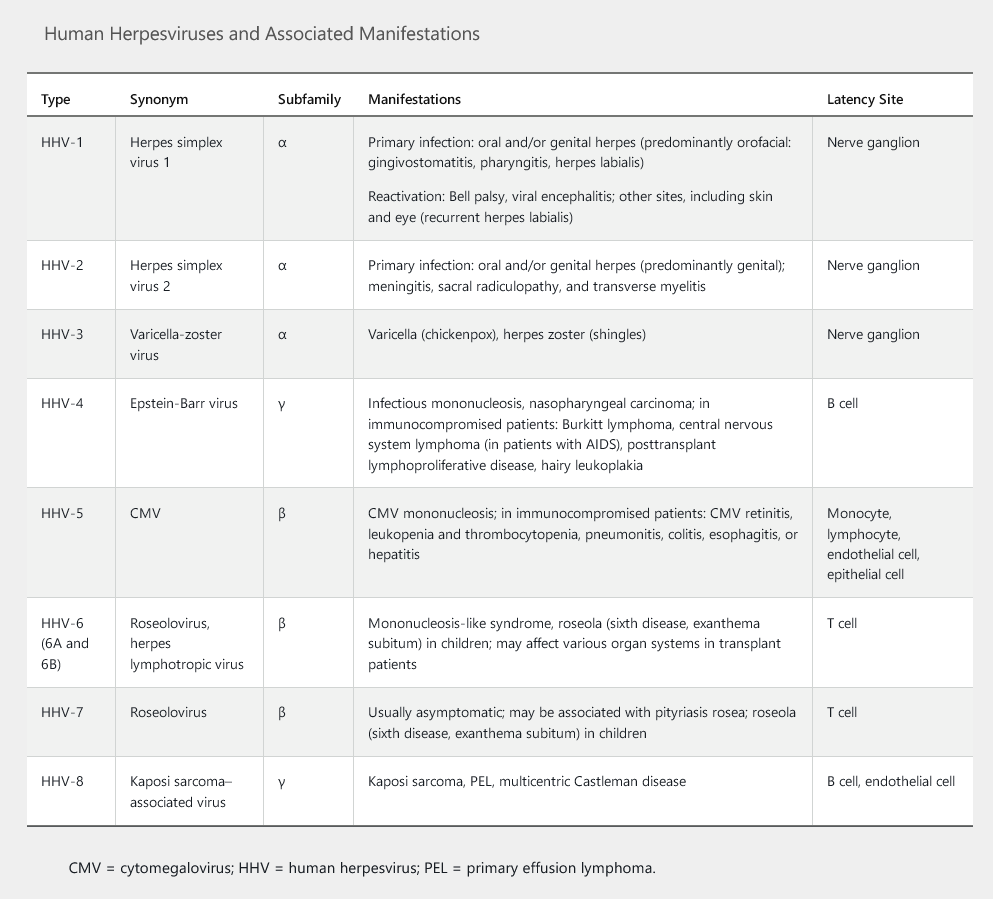

Human herpesviruses (HHVs) are a group of eight DNA viruses (Table 68). In humans, infection with HHV results in lifelong viral latency with the possibility of reactivation and oncogenesis. HHV can be transmitted by physical or sexual contact during active infection or through asymptomatic shedding of the virus (in saliva, semen, or cervical secretions); other routes include blood transfusion, organ transplantation, or maternofetal transmission. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is the only HHV that can be transmitted by the airborne route; it is also the only HHV with a vaccine that produces protective humoral immunity. Antivirals are available for some HHVs, and immunoglobulin therapy is available for cytomegalovirus and VZV.

Herpes Simplex Virus Types 1 and 2

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 infection is transmitted by oral-oral or oral-genital contact. It typically causes oral ulcers and affects 90% of adults (see MKSAP 18 Dermatology). During stress, severe illness, or immunosuppression, patients may experience recurrence of oral stomatitis or esophagitis. The incidence of primary genital infection by HSV-1 is increasing (see Sexually Transmitted Infections). HSV-1 is the most common cause of viral encephalitis (see Central Nervous System Infections).

HSV-2 is sexually transmitted and typically causes genital and rectal ulcers with or without proctitis. HSV-2 affects approximately one sixth of adults in the United States and can also cause recurrent benign lymphocytic meningitis (Mollaret meningitis), myelitis, sacral radiculopathy, and neonatal infection or death (maternofetal transmission in primary genital infection). HSV-1 and HSV-2 can cause herpetic whitlow (on fingers), herpes gladiatorum (a skin infection typically associated with contact sports), keratoconjunctivitis, retinitis, and erythema multiforme.

HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections can be treated and suppressed with oral nucleoside analogues (acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir). Topical antiviral agents (trifluridine and vidarabine) are used for herpetic keratitis. Intravenous acyclovir is used for severe mucocutaneous disease, disseminated infections in immunosuppressed persons, esophagitis, and suspected HSV encephalitis.

Varicella-Zoster Virus

Overview

VZV (HHV-3) is transmitted by inhalation and colonization of the respiratory tract, with subsequent viremic dissemination to skin, liver, spleen, and sensory ganglia (varicella, or chickenpox). VZV establishes latency in the ganglia and can later reactivate, causing herpes zoster (shingles), especially in adults older than 60 years or in immunosuppressed patients. Contact and airborne precautions should be used for all hospitalized patients with varicella, for patients with disseminated herpes zoster, and for those with dermatomal zoster who are immunosuppressed.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Primary varicella infection (chickenpox) presents with a febrile pruritic vesicular rash affecting the skin and mucocutaneous surfaces (oropharynx, conjunctiva, genitals); the rash commonly begins on the face and trunk, then spreads to the extremities (centrifugal distribution). Lesions may comprise macules, papules, vesicles, and scabs in different stages of development. Skin lesions may become superinfected with Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus (impetigo). Most children recover without sequelae, but adults may develop pneumonia, encephalitis, hepatitis, and cerebellar ataxia.

Herpes zoster typically causes a painful vesicular rash that follows a dermatomal distribution that does not cross the midline (see MKSAP 18 Dermatology). Young patients presenting with herpes zoster should be tested for HIV. Immunosuppressed patients can present with multiple dermatomes affected or with disseminated disease. Postherpetic neuralgia, defined as neuropathic pain lasting more than 1 month after resolution of the vesicular rash, is the most significant complication of herpes zoster. Other complications include herpes zoster ophthalmicus with visual loss, Ramsay-Hunt syndrome (vesicular rash in external ear associated with ipsilateral peripheral facial palsy and altered taste), pneumonia, hepatitis, and central nervous system complications such as meningitis, encephalitis, myelitis, and stroke caused by vasculitis (see Central Nervous System Infections).

Involvement of the geniculate ganglion may cause herpes zoster oticus, also known as the Ramsay Hunt syndrome, characterized by pain and vesicles in the external ear canal, ipsilateral peripheral facial palsy, and altered or absent taste. Patients may also experience hearing loss, tinnitus, and altered lacrimation. Most experts consider Ramsay Hunt syndrome to be a polycranial neuropathy, with frequent involvement of cranial nerves V, IX, and X. A vesicular rash may be absent in patients with VZV (zoster sine herpete) and should not deter physicians from ordering polymerase chain reaction testing for VZV.

Varicella or herpes zoster can be diagnosed clinically by the typical vesicular rash and confirmed with VZV PCR testing of the base of a vesicular lesion. VZV is underdiagnosed in the absence of a rash (zoster sine herpete); in such cases, cerebrospinal fluid serologic (VZV IgM and IgG) and PCR testing can be used to diagnose the infections.

Management

Antiviral therapy (acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir) speeds recovery and decreases the severity and duration of neuropathic pain if begun within 72 hours of VZV rash onset. Intravenous acyclovir should be used for immunosuppressed or hospitalized patients and those with neurologic involvement.

Vaccination is the most important preventive strategy (see MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine). Postexposure prophylaxis should be provided to susceptible persons (VZV IgG negative); postexposure varicella vaccination is appropriate in immunocompetent persons, and varicella-zoster immune globulin should be used in immunocompromised adults and in pregnant women.

Epstein-Barr Virus

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (HHV-4) is highly prevalent; serologic studies show evidence of previous EBV infection in almost all adults. It is most commonly transmitted by saliva and is the main cause of infectious mononucleosis in children and adolescents. Patients present with fever, severe fatigue, exudative pharyngitis, cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly. Atypical lymphocytosis and aminotransferase level elevations are clues to the diagnosis, which is established by the presence of heterophile antibodies (Monospot test) or IgM to the EBV viral capsid antigen. The Monospot test result may be negative in the first week of illness. Treatment is supportive, with no role for acyclovir; glucocorticoids may be given to patients with autoimmune hemolytic anemia, central nervous system involvement, or tonsillar enlargement with a compromised airway. EBV is associated with the development of T-cell and B-cell lymphomas, Hodgkin and Burkitt lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in solid organ transplantation.

Human Cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus (HHV-5) infections are most commonly asymptomatic but may present with a mononucleosis-like syndrome without pharyngitis and with negative heterophile antibody results. Cytomegalovirus may be transmitted through the placenta (congenital cytomegalovirus), breastfeeding, saliva, blood transfusion, or organ transplantation (cytomegalovirus-positive donor to cytomegalovirus-seronegative recipient). Approximately 60% to 90% of adults have latent cytomegalovirus infection with reactivation of disease more common in immunosuppressed persons (those with AIDS, transplant recipients, those receiving glucocorticoid therapy). Cytomegalovirus can cause retinitis, pneumonitis, hepatitis, bone marrow suppression, colitis, esophagitis, and adrenalitis in immunocompromised persons. Immunocompetent patients occasionally also present with colitis.

Because cytomegalovirus can cause a myriad of clinical manifestations, a high index of clinical suspicion is important. Diagnosis is commonly confirmed with molecular tests, such as PCR testing of serum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, or cerebrospinal fluid, or by demonstrating typical cytopathic “owl's-eye” intracellular inclusions on biopsy specimens (Figure 25). Pathologic diagnosis is confirmed by cytomegalovirus immunostains. Serologic assays have limited diagnostic utility because most adults are seropositive; however, they are performed routinely in pretransplant evaluations to assess the risk of cytomegalovirus reactivation after transplantation and to determine appropriate prophylaxis.

Antiviral therapy with intravenous ganciclovir or oral valganciclovir is used in immunocompromised patients or in immunocompetent patients with severe disease. Oral valganciclovir is also used as prophylaxis or pre-emptive therapy (treat if the PCR serum testing result is positive) in transplant recipients. Foscarnet and cidofovir can be used in instances of ganciclovir resistance or intolerance.